Could he be elected to the Hall of Fame had he not broken the color barrier?

Jackie Roosevelt Robinson was ahead of his time. Emerging almost 20 years before the Civil Rights movement, Robinson is known to African-Americans as a pioneer. He played second base in the Negro Leagues until age 25, when Branch Rickey, then the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, discovered the talented prospect. Rickey, known as “the mahatma” for his devout faith, had been looking for the right guy to break the “color barrier” for years and felt Robinson fit the bill. After successfully proving himself in the Minors, Jackie Robinson shocked the world when he was called up to the Dodgers for the 1947 season at the ripe age of 28.

Robinson made an immediate impact, though initially it was not positive. By the end of April, he was only batting .225, but still garnered much attention from the media. He improved throughout the year and ended strong. He finished the season batting .297 with 125 runs scored, 29 stolen bases, and only 36 strikeouts. For both his bravery and performance, Jackie Robinson was awarded the inaugural Rookie of the Year Award and also finished fifth in MVP voting.

His career took off from there: after a similar 1948 campaign, Robinson exploded in 1949. Other than runs scored, he had career bests in every major offensive statistic. He batted a league leading .342 with 122 runs scored, 124 runs batted in, 37 stolen bases, 203 hits, 86 walks, and only 27 strikeouts. 1949 was obviously Robinson’s best year, and he was awarded the MVP for his feats. The second baseman would have many more notable years, but none comes close to 1949.

In 1956, his 10th and final season, Robinson had a rather pedestrian showing for the second consecutive year, and afterwards, he decided to call it quits—to the chagrin of fans across the country. Over the years, there has been much speculation as to the reason for Robinson’s retirement. Jules Tygiel, author of the acclaimed biography Extra Bases: Reflections on Jackie Robinson, Race, and Baseball History states that “upon his retirement in 1956, Robinson…had already begun to manifest signs of the diabetes that would plague the rest of his life.” Others believe he withdrew from baseball due to his refusal to play for his new team, the New York Giants. Regardless, Robinson had a successful ten-year tenure with the Dodgers.

Robinson was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame (HOF) in 1962, his first year of eligibility. The question is, upon what merit was he elected? Was it for his playing ability and leadership of the Dodgers? Or was it for his resolve in breaking the color barrier? Or both?

The middle question is quite easy to answer: Robinson’s boldness and grit merit him a spot in baseball’s hallowed grounds regardless of his playing career. He received an overwhelming amount of hate mail and death threats, and the typical man would have given up from the start. So the question now becomes, could Robinson’s playing career alone have gotten him accepted into the HOF?

We’ll look at the conventional stats. Basically, Robinson had eight great years in the MLB: 1947-1954. During this span, there were few people in the MLB as productive offensively as Robinson. He was in the top 10 in batting average six times, in the top 10 in runs scored seven times, in the top 10 in hits five times, and selected to six all star games. He also was in the top 10 in stolen bases seven times during that period. Traditionally, Bill Mazeroski is known as the greatest defensive second baseman ever, but had Robinson played longer, he would have given Mazeroski a run for his money. Robinson led the league in fielding percentage among second basemen every year from 1948-52, which were his only years that second base was his predominant position. Moreover, Robinson’s stats probably would have been even more impressive had he not been dealing with hate mail and death threats.

Though Jackie Robinson had all of that single season success, his career numbers are lacking. He did bat .311, good for 100th place all time, but he is behind players like Nomar Garciaparra and Magglio Ordonez, neither of whom will get elected into the HOF. Robinson’s highest career ranking is on base percentage, in which he ranks 36th all time. Other than that, he is not in the top 100 in any major offensive statistic. While he missed much of his prime, entering the league at 28, so did Ted Williams, Bob Feller, and Joe DiMaggio. Still, their career stats are far more impressive than Robinson’s.

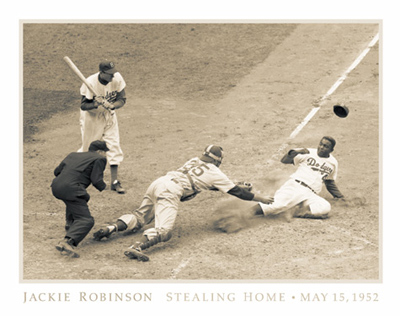

Robinson’s Dodgers won the pennant six times during his tenure, and, in the World Series, they lost to the New York Yankees five times. They conquered their only World Series trophy in 1955, avenging their losses to New York. However, Robinson was hardly superhuman in the Fall Classic. He batted lower than .200 in half of those series, and he never stole more than two bases. The nostalgic baseball fan would now point out Robinson’s memorable steal of home in Game 1 of the ’55 Series. While that was one of the most remarkable moments in World Series history, the rest of that Series was lackluster: he batted an anemic .182, and had no more stolen bases during the remainder of the Fall Classic. Overall, Robinson batted just .234 in his six career World Series appearances, and swiped only six bases. Clearly, Robinson’s two statistical weaknesses are his career and postseason stats.

So we have a problem: his single season stats are herculean, but his career and postseason stats are not there. Renowned statistician Bill James ran into the same problem as I have, so he invented four statistics specifically for judging a player’s HOF status: Black Ink Test, Gray Ink Test, Hall of Fame Monitor, and Hall of Fame Standards. The Black Ink Test rewards a player for leading his league in any major statistic, while the Gray Ink Test rewards a player for coming in the top ten in any major stat. Hall of Fame Monitor rewards a player for having statistics higher than a benchmark total (i.e. above a .300 batting average) in a single season, while Hall of Fame Standards does the same thing, except for career totals.

So when you test Jackie Robinson with these stats, he appears to be a borderline HOFer. The average HOFer scores 144 on the Gray Ink Test, while Robinson scored 121. Similarly, a likely HOFer scores 100 on the Hall of Fame Monitor Test, and Robinson scored 98. In James’s other two stats, Robinson’s scores are very similar. According to these stats, it appears Robinson is in the lower echelon of HOFers.

All in all, my best judgment says that, based solely on statistics, Robinson would have eventually reached the HOF, but not on the first ballot. This, of course, is a moot argument because regardless of his stats, Jackie Robinson was a pioneer for baseball and for African-Americans throughout the entire country. His efforts toward improving the quality of life for African-Americans were ahead of his time, and he deserves to be in the HOF, whether or not his stats show it.

5 Responses

Nice job Mitch! I agree with you entirely!

Well Mitch,you put a lot of things in perspective here and I agree with you and your references………personally knowing you,well, a long time,and knowing your love of baseball…..I totally respect you opinion. One thing that you should add (that is the beauty of the internet) is your experience of being around the game at its roots,the same place Jackie learned the game, in the sandlots…known for being a “tough out”..unfortunately we as humans like to “measure”, always trying to put a quantitative analysis on individuals and their accomplishments with some caveat as to when and under what conditions these measurements were taken. If you cannot measure it then it seems we are open to controversy……Leadership is the ability to inspire hope,and hope is the catalyst that inspires personal achievement…..unfortunately you cannot measure it (leadership) only its results. But Jackie is a “shoe in” no questions asked to the HOF with his leadership….he inspired all those around him, he led his team to those pennants. He made all those around him better on and off the field,yes he made outs just like everyone else,but he made them “tough outs”……. HOF no doubt

Thanks for reading my article Andy! Like you said, we do like to put a qualitative value to measure just about everything, but to do so with leadership and being a “tough out” is nearly impossible. As a high school kid, I really just have to go by what I know as a fact, which is statistics. I have a new article coming out hopefully by next Tuesday; I think that you will definitely like the topic. Also, when baseball season comes around, and I’m coming to Reds games, I will definitely consult topics and ideas with you.