Editor’s Note: This was originally posted on Bucs Prospects back on 12/9/2010.

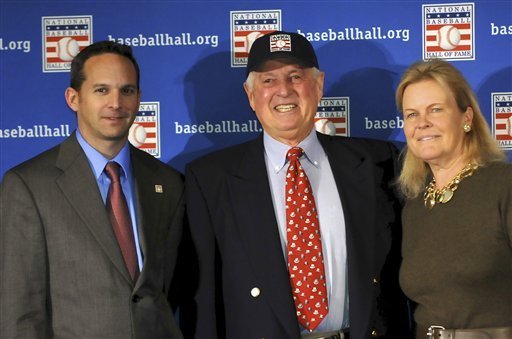

Pat Gillick’s induction into Baseball’s Hall of Fame is not only well-deserved, but it comes with perfect timing. With today’s emphasis on intellectuals over baseball men and numbers over people, it’s refreshing for a purist like myself to see an old school scout like Pat Gillick be given the ultimate honor.

What I sincerely hope is that it leads fans, media, and those in front offices across Major League Baseball to reflect on and learn from Gillick’s career. He built the expansion Toronto Blue Jays into an American League power for two decades. Gillick brought four different franchises to the playoffs and won three World Series trophies. That’s what will be displayed on his plaque in Cooperstown, but the genius of the man goes much, much deeper and I’m disappointed in how few of today’s organizations follow his philosophies in 2010. Older fans would be stunned by how many young baseball executives know nothing about Pat Gillick, what he’s done, and how he’s done it. His philosophies have sadly been cast aside.

It was different in the 1980s and early 1990s. At that time, it was very clear that Gillick’s Blue Jays were the model organization and other teams were quick to imitate. The 7-team American League East was the dominant division throughout the 1980s due in no small part to its group of exceptional general managers. There was Bill Lajoie(Detroit Tigers), Harry Dalton (Milwaukee Brewers), Lou Gorman (Boston Red Sox), and Hank Peters (Baltimore Orioles) in the same division with Gillick at the same time. Like Gillick, the four of them were grizzled veterans with extensive scouting and player development backgrounds who’d worked their way up the ladder believing wholeheartedly in the same philosophy.

The Blue Jays were not only contenders from 1982-1994, but they also had the best farm system in the game. Pitchers, hitters, base-stealers, gold glovers, international players, you name it, they were loaded at every level. If you were going out to see a Blue Jays minor league affiliate, chances were good you’d see some serious talent that day.

It’s one thing to have a good big league team or to have a loaded minor league system, but to have both at the same time year after year is a rare and tremendous accomplishment. The Blue Jays drafted well and were pioneers in Latin America, but they were also tremendously successful finding talent under rocks in the Rule V Draft (see 12/6 story, The Rule V Draft on Thursday: The challenge of beating other teams on their own farm).

After years of competing but falling short of a championship, Gillick took heat from the Toronto media for his inability to seal a blockbuster deal. Some even took to calling him “Stand Pat” Gillick. It was an unfair nickname to begin with, but even so, Gillick turned that reputation on its ear with a series of brilliant transactions. His trade that nettedRoberto Alomar and Joe Carter from the Padres vaulted the Jays to consecutive championships in 1992 and 1993.

In the last decade, you’ve surely heard the Blue Jay management’s incessant complaints about competing in the same division as the Red Sox and Yankees. Well, the Red Sox and Yankees were after-thoughts in the A.L. East during the Gillick Blue Jay era. The Yankees didn’t go to the postseason once between 1982 and 1993 while the Blue Jays went five times.

Pat Gillick won’t take the credit, but he was the reason. The Labatt ownership definitely helped, providing him excellent financial resources. Credit must certainly be given to his staff as well, but Gillick is the one who hired and listened to them. Before you knew it, this expansion baseball team from a hockey-crazed Canadian metropolis was leading MLB in attendance while whipping the Yankees, Red Sox, Tigers, Orioles, and everyone else year after year.

Bobby Cox took the Pat Gillick philosophy to the National League. After managing the Blue Jays for Gillick in 1985, Cox accepted the GM job for the Atlanta Braves and laid the foundation for their unprecedented 14 consecutive first-place seasons (1991-2005) by emphasizing hardcore scouting, drafting, and building from within. John Schuerholztook over GM duties in 1991, with Cox going to the dugout, and perpetuated the Braves historic run with the same ideology.

But something happened in the 2000s. Inexplicably, the Gillick model went out of style. He was a hardened baseball man who grew up in both scouting and player development with the Astros and Yankees and went on to win championships by valuing people over numbers, but younger people of his background were getting ignored for the plum positions. Somehow, Gillick’s success was forgotten by MLB owners who wanted a general manager with a much different background and an entirely different philosophy that de-emphasized anything subjective in favor of quantified analytics.

Suddenly, Billy Beane and the Oakland A’s became the new models, after belying a bottom-third payroll with great on-field success in the early 2000s. Owners, fans, and media all wondered aloud why their teams couldn’t do what Beane was doing. As Gillick was mimicked during the 1980s, Beane became the envy of every owner in the early 2000s.

While it is understandable why Beane would draw interest, it’s puzzling to me how quickly owners and front office personnel turned their backs on a model that had been even more successful for so much longer. Gillick came back to be the GM of the Orioles (1996-1998), Seattle Mariners (2000-2003), and Philadelphia Phillies (2006-2008) and with only minor tweaking of his strategy, the old man was immensely successful in what was supposed to be the “Moneyball” era.

I’ve come to believe that a number of teams jumped the gun on Moneyball. Beane was clearly successful for about seven years, but Gillick had built playoff teams over three decades. Had the teams who cleaned house and sold their souls to Moneyball known that the A’s would go four years in a row of winning the division and getting knocked out in the first round, that they’d never get to the World Series, and that they’d spend the last part of the decade rebuilding again, would those teams have jumped on the bandwagon so quickly?

Beane was quite savvy with the media and certainly the bestselling book with Michael Lewis brought great attention to his philosophies. Gillick, on the other hand, was not one to look for the spotlight and while working for the Blue Jays, he refused to give information to Baseball America and other outlets which undoubtedly led to less favorable media coverage. Beane, on the other hand, catered to BA and other media outlets and they in turn were quick to praise and publicize his success.

Not that Gillick cared, and for me that’s the greatest part of his legacy, and what I wish today’s executive would pay attention to. It was never about Pat Gillick, wherever he went. It was never about putting his stamp on an organization, bringing in his own people and his own players, and filling his cabinet with “yes men”. Gillick didn’t have the ego of today’s general manager, but that’s not the reason he operated in such manner. Gillick operated that way because it was good business.

He had a chance to prove it after leaving Toronto. The first thing modern general managers do when they take a job is fire everybody affiliated with the previous regime and it rarely has anything to do with the incumbents’ qualifications. Gillick made it a point to evaluate whomever he inherited and if the scouting or farm director had proven himself effective, Gillick wanted him on his side whether he was the one who hired him or not.

Gillick did it three times, in Baltimore, Seattle, and Philadelphia. The 1995 Orioles were a veteran team that had stumbled. Gillick kept Gary Nickels as his scouting director, signed a few free agents, kept together the core ofMike Mussinas and Cal Ripkens, and went to the ALCS the next two seasons. He was forced to trade Ken Griffey Jr. upon taking the Mariners job in 2000, but somehow came on top of that deal, kept most of his staff together, and then brought Seattle to the ALCS for consecutive seasons just like he did for Baltimore.

And of course in Philadelphia, Gillick inherited considerable talent from former GM Ed Wade. The Phillies had good teams for much of the 2000s, but they just couldn’t get to the playoffs. Gillick did almost nothing to change scouting or player development because he recognized they were among the best in the game. There was no thought whatsoever about dismantling a promising core infield of Chase Utley, Jimmy Rollins, and Ryan Howard just because they weren’t “his” players.

Gillick made some important moves and tweaks, but he was again careful not to undo the good that came before him. And how fitting that in his retirement year of 2008, Pat Gillick went out as a World Series Champion?

But my most stirring memory of that season is something else, something that sums Pat Gillick up as a professional, something that makes him different from almost every other person I know in Baseball because not only did he say what he said, but he meant it.

In the midst of a champagne-soaked celebration, the FOX network descended upon the victorious 71 year-old general manager.

Pat Gillick had every reason to gloat. Instead, he thanked Ed Wade for building the team and putting him in position to experience the thrill of winning a World Series.

I’ve written over 1,500 words, but that right there is all you need to know about Lawrence Patrick Gillick.