Tempers flared on a muggy summer night in July of 1986 on the artificial turf of Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. With one out in the bottom of the 10th inning of a 3-3 tie with the Mets, 45-year-old Pete Rose singled to center for the Reds. Eric Davis, in his first full season with the Reds, was sent in to pinch run for the aging hit king. Davis stole second then immediately tried to steal third on the next pitch. Popping up from his slide, Davis found himself face-to-face with the Mets’ feisty third baseman Ray Knight, whom he gave a slight push. Knight responded with a swing-and-miss right hand punch to Davis’ face and the bench clearing brawl was on. The dust and dirt of the third base cutout formed a yellowish-brown cloud amidst the brawl as Mets team leader Keith Hernandez, attempting to be a peacemaker, was battered and bounced around inside the middle of the melee.

After the dust settled, Buddy Bell and Dave Parker of the Reds hit back-to-back singles in the bottom of the 12th inning, putting runners on first and second with no one out. Reds pitcher Carl Willis then attempted a sacrifice bunt and placed the ball perfectly in the shallow infield Bermuda Triangle between the catcher, pitcher and first baseman. However, Hernandez pounced on the ball like a cat and threw it off-balance to third base to get the lead runner. Gary Carter, playing third base in place of the ejected Knight, was quite possibly startled that Hernandez even got to the ball but nevertheless relayed it to second to get the rare 3-5-4 double play and kill the inning.

Hernandez went 3-for-5 at the plate that night with two doubles and got on base two other times via walks. Additionally, it was Hernandez’ deep line drive to the warning track in right that popped out of Parker’s glove for a two-run error that tied the game in the ninth, 3-3. If ever there was a case that could be made for Keith Hernandez’ election to the Baseball Hall of Fame, that game on a Tuesday night in Cincinnati on July 22, 1986 encapsulated everything in one nice little package with a pretty bow on top.

Hernandez never received more than 10.8% of the votes cast by the Baseball Writers Association of America for election to the Hall of Fame (75% is required). In his last year of eligibility in 2004, he got less than 5% of the votes. He also has not been elected by the BBWAA Veterans Committee who took over his candidacy in 2011. Really? He’s not even a borderline candidate?

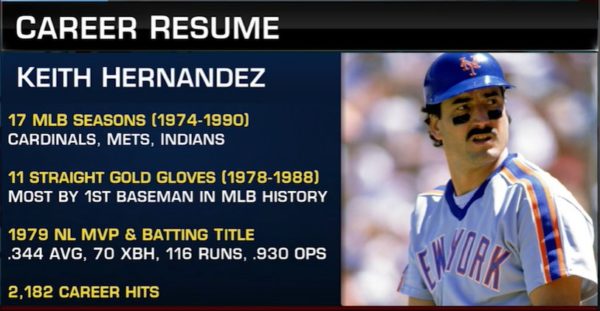

Hernandez checks many of the boxes to be considered a Hall of Famer even though most of the BBWAA have failed to check Keith’s box on their ballots. He won a co-MVP award (tied with Willie Stargell) as a St. Louis Cardinal in 1979 with a signature season. He won the batting title (.344), led the league in doubles (48) and runs scored (116) and drove in another 105 runs with a .417 on-base percentage and a 7.4 WAR. He wears two World Series rings from the 1982 Cardinals and the 1986 Mets. He was involved in a franchise-transforming trade in June 1983 when the Cardinals traded him to the Mets, culminating in a mini-dynasty from 1984 to 1989 during which the Mets won a World Series and finished either first or second in the division every year. He became the team leader of the franchise, somehow uniting at best a diverse, at worst a wayward group of characters into an on-the-field juggernaut focused on winning. He is widely considered to be the preeminent defensive first baseman of his generation, winning eleven Gold Gloves. He affected the entire infield defense of a championship team that cannot be measured. All his fellow infielders were able to cheat to their right because of his uncommon range, plugging otherwise gaping holes in the infield. He has become known to a whole new generation of baseball fans as a longtime broadcaster for the Mets and a social media darling with his beloved feline Hadji.

It seems that Hernandez’ candidacy would appeal to the sabermetrically-inclined modern voters as well. He was an on-base percentage monster, finishing over .400 five times and between .375 and .400 four other times between 1977 and 1987. During the same time frame, he had an OPS over .900 twice and between .800 and .900 eight times. His lifetime 59.4 WAR compares favorably with Hall of Famers Harmon Killebrew (60.3), Vladimir Guerrero Sr. (59.5), Mike Piazza (59.5) and Yogi Berra (59.4). One of the most popular single sabermetric measurements for a hitter is wRC+ which is the number of runs created per plate appearance by a hitter where the league average is 100. Hernandez’ lifetime wRC+ is 131 meaning that over the course of his career, he was 31% better at creating runs than the league average. That figure compares favorably with Rod Carew (132) and exceeds fellow first baseman Tony Perez (121), both of whom are Hall of Famers.

It’s likely that Hernandez did not get elected by the BBWAA because of two factors. First, his cocaine use became a matter of public record when he testified at the trial of former Philadelphia Phillies caterer Curtis Strong in 1985. For better or worse, voters have considered a player’s off-the-field transgressions when filling out their ballots. But consider that the Mets retired Hernandez’ number 17 last summer and placed it high above Citi Field alongside Gil Hodges (14), Willie Mays (24), Mike Piazza (31), Jerry Koosman (36), Casey Stengel (37) and Tom Seaver (41). Are we to believe that the New York Mets have a lower standard for honoring their former players than the BBWAA has for electing players to the Hall of Fame? Wouldn’t the Mets also take into consideration a player’s off-the-field behavior before retiring their number and placing them on the same level as Tom Seaver and Gil Hodges?

Another factor dissuading Hall of Fame voters was no doubt the fact that Hernandez was not a power-hitting first baseman. His home runs per-162-game average was only 13. But Keith is a victim of his era. His career is almost identical to that of George Sisler who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939. In 2,055 games in his career, Sisler hit 102 home runs with 1,178 RBI, 1,284 runs scored, also won one MVP (in 1922) and was also considered to be the best defensive first baseman of his generation. Hernandez hit 162 home runs, 1,071 RBI and scored 1,124 runs in 2,088 games. Why was Sisler elected to the Hall of Fame and Hernandez was not? Because Sisler played in the dead ball era of the 20’s and Hernandez played during the modern home run era. But if you consider statistics like WAR, OPS and wRC+ to be true evaluations of a player’s worth, then Hernandez was just as valuable and historically relevant as many power-hitting first baseman who have been elected to the Hall of Fame. For instance, no one doubts the Hall of Fame credentials of Tony Perez. Yet Perez’ career War (58.9) was lower than Hernandez (59.4), his career wRC+ (121) was lower than Hernandez (131), he had the same number of seasons with an OPS of over .900 (2) and only had an OPS between .800 and .900 five times compared to the eight times for Hernandez.

Keith Hernandez belongs in the Hall of Fame. If it ever happens, let’s hope that Hadji is carved into the plaque as well.

One Response