When baseball implemented a revenue sharing plan as part of their collective bargaining agreement in 1997, the premise behind the plan was that it would create a more competitive atmosphere between all teams in baseball. So rather than the elite, large market teams such as the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox who can continue to pay top dollar for free agents, revenue sharing allows smaller market teams to spend on player salaries as well.

According to the revenue sharing plan implemented in the collective bargaining agreement of 2002, every team pays in 31 percent of their local revenues and that pot is split evenly among all 30 teams. In addition, a chunk of MLB’s Central Fund — made up of revenues from sources like national broadcast contracts — is disproportionately allocated to teams based on their relative revenues, so lower-revenue teams get a bigger piece of the pie.

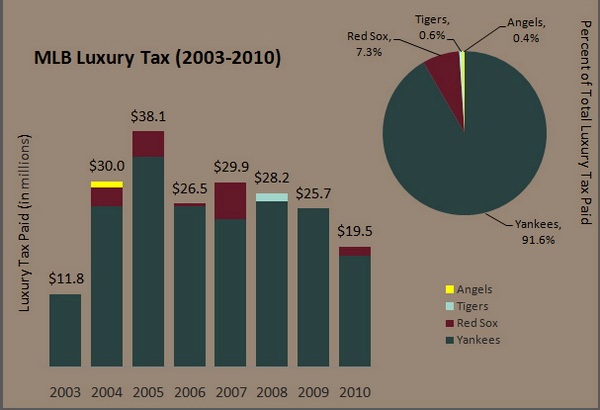

Also, teams who exceed the set payroll limits pay into the pot a luxury tax, which is then distributed to the lower revenue teams. For instance, in 2008 the New York Yankees, according to the Wall Street Journal, paid out $21.6 million in luxury tax money. That money was distributed to the teams with the lowest payrolls in the league.

Can teams use revenue sharing to improve the quality of the product on the field? There are at least two instances where teams clearly used the extra money to improve.

In 2003, the Detroit Tigers were the worst team in the league, and one of the worst all-time, with a record of 43-119. The club was 13th out of 14 teams in attendance, and easily qualified for extra revenues at the time. The Tigers used the money to sign catcher Ivan Rodriguez and right fielder Magglio Ordonez, who were key components to the team that won the American League pennant just three years later.

In 2007, after a sixth straight losing season, the Colorado Rockies used all of the $16 million they received in the revenue sharing plan and put it all toward payroll. The following season, the Rockies won 13 of their last 14 games to force a one-game playoff with the San Diego Padres to determine the Wild Card in the National League. The Rockies won that playoff game, and then swept their way into the World Series before eventually losing to the Boston Red Sox.

So there are certainly instances where revenue sharing has been implemented in the way that it was intended.

However, there have been far too many circumstances where revenue sharing clearly hasn’t worked, and smaller market teams have essentially used the extra money to pad their profits.

The Florida Marlins were on top of the world in 2003, having beaten the New York Yankees in the World Series in six games. Their payroll that particular season was $54 million. However, just three years later, after allowing homegrown talent to walk away without offering contracts and trading World Series heroes Josh Beckett and Ivan Rodriguez for much cheaper players, the Marlins’ payroll dropped to $14.9 million, which at the time was just 20 percent of the league average payroll of $78 million. Yet, the Marlins had received almost $31 million in revenue sharing money that year, more than double their actual payroll.

The Tampa Bay Rays were also guilty of receiving over $30 million in payroll dollars for five straight years between 2002-2006, yet their average payroll during that time was just $27 million, and the team reported a profit of an average of $20 million during that same time.

The biggest problem with the current revenue sharing plan is the definition of how the money is to be used is quite vague. All the agreement states is that the money is to be used to “improve the product on the field,” and MLB has done little to enforce that policy over the years.

The simplest solution is to change the language. Rather than stating that revenue sharing allotments should be used to “improve the product on the field,” the agreement should state that “all revenue sharing allotments must be used on player payroll.” It’s simple, cut and dry, and can be easily enforced by MLB.

There is no question that revenue sharing rules should indeed change, but to start, simple language needs to be fixed. What do you think?

One Response

“Also, teams who exceed the set payroll limits pay into the pot a luxury tax, which is then distributed to the lower revenue teams. For instance, in 2008 the New York Yankees, according to the Wall Street Journal, paid out $21.6 million in luxury tax money. That money was distributed to the teams with the lowest payrolls in the league.”

—————–

Absolutely incorrect.

The luxury tax gets paid to the league. Not to the other teams. 50% goes to fund player benefits (NOT salaries, league-wide benefits), 25% goes to develop baseball in countries where there is no high school baseball, and 25% into the “Industry Growth Fund”.

The NBA luxury tax money is distributed to each team. That does not happen in the MLB.