Visits: 1

By Rocco Constantino

When sifting through the influential players in the segregation of baseball, the names Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and Satchel Paige are always mentioned at the forefront. What sometimes gets lost in the shuffle is that there were really hundreds of players who should be considered pioneers in the integration of the sport. Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947 didn’t just flip a switch of acceptance, signaling to all that the game was now integrated. It took 12 years before every single Major League team had been integrated and between Robinson’s debut and Pumpsie Green’s first appearance with the Boston Red Sox on July 21, 1959, so many black ballplayers faced similar obstacles as the Civil Rights movement was shaping America and baseball struggled with full acceptance of integration.

One of those players who continued to carry the torch for full acceptance was Fred Valentine. When Valentine graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Memphis, Tennessee in 1953, only seven Major League teams had integrated. The most recent had been Minnie Minoso, who debuted as the first Chicago White Sox black ballplayer on May 1, 1951. Integration was so slow that even with the success of players Robinson, Doby, Monte Irvin and Don Newcombe, not a single team integrated in 1952.

Although Valentine had a deep love of sports, he and his friends had to make his own opportunities while growing up in Memphis. “They didn’t have Little League for young black kids,” said Valentine in an interview for the book 50 Moments that Defined Major League Baseball. Instead, Valentine and his friends would play in sandlots and streets in his neighborhood, getting in a game wherever they could.

Valentine didn’t have the luxury of seeing any Major League games in person, but when Negro League barnstorming tours came through Memphis, he and his friends would go watch. They also used it as an opportunity to help their own games. “We’d go and watch when they came through Memphis, but first we’d hang outside the ballpark. We used to chase foul balls and keep them to be able to use in our own games. Once we had enough, we’d go in and watch.” This was during a time when Satchel Paige and Hank Aaron were playing in the Negro Leagues, and Valentine saw them both.

As he got older, Valentine developed into a terrific athlete and was a star in baseball at Booker T. Washington. Even though so few teams had integrated at that point, Valentine drew interest from professional scouts, but, at the urging of Valentine’s parents, he valued the opportunity to pursue a college degree. It was that urging that led Valentine to make a request that was rare for anybody to make, let alone a black baseball player in the 1950’s.

“One of the requests that I had when I had the chance to sign a pro contract was that the team also pay for me to pursue a college degree,” said Valentine. “I wanted to go to college as much as I wanted to play ball, and this was a chance for me to be able to do so. I told the Cardinals I would sign on the condition that they paid for four years of college for me and they told me they never heard of such a thing, so I passed on the chance to play pro ball and went to Tennessee State instead. The times weren’t right then, but that was the turning point of my life”

While at Tennessee State (then Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College), Valentine joined the football team and became a start quarterback under legendary coach Henry Kean. Kean, who compiled a coaching record of 166-33-9 over his career, recognized Valentine’s athleticism and inserted him as the starting quarterback. He was the team’s top offensive player in 1953 and 1954 and began to also draw attention as a professional football prospect. That career was sidetracked again as a result of the times.

“I wanted to be a professional quarterback, but they told me that black athletes couldn’t be quarterbacks,” said Valentine, who passed for 1,279 and 14 touchdowns in 1954. “They wanted me to switch to defensive back or running back, but that wasn’t my thing. So I went back to baseball.” Valentine played both offense and defense for Tennessee A & I and was fifth in the nation in total offense for small-colleges.

As a pro baseball prospect, Valentine drew interest from the Baltimore Orioles, St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates, ultimately signing with the Orioles. He spent three full seasons in the minors before getting his chance with the Orioles at the end of the 1959 season. Upon his call up, he was put right into the third spot in the batting order and played right field. He got his first Major League hit, a bunt single to third, off All-Star Billy Pierce four days later.

After enduring many of the same discrimination and hate that all of his predecessors faced, especially during a season in the Carolina League for the Wilson Tobs in Wilson, North Carolina, Valentine was lucky to have a number of mentors and supporters in the Majors. By the time he came up, Brooks Robinson was just about to breakout as a star and Bob Boyd, the first black player to sign with the Chicago White Sox, was also on the team. Valentine listed them as influential people in his success in the majors.

Valentine ended up playing seven years in the majors with 1,660 plate appearances. His best year came in 1966 when he hit .276 with 16 home runs. That year he received MVP recognition, finishing higher in the voting than players like Carl Yastrzemski, Tony Conigliaro and Jim Fregosi. However, his real legacy is the class he showed while battling through racism to reach his goals.

In a profile on SABR.com, Valentine relayed a story from when he was a star player in the Carolina League. Most stadiums were still segregated and when fans showed up to watch his team from Wilson play in Greensboro, they found the stands for black patrons nearly in disrepair. He suggested to the general manager that they integrate the seating sections to allow all fans to sit together. He reasoned that all the people in the town knew each other anyway. Because Valentine was so respected for his play on the field and his class off of it, the general manager took his advice and, for the first time, all fans were able to sit together.

“Racism was strong during that time,” said Valentine. “Most teams hadn’t fully accepted integration yet, so I went through the same things many black players did. It was just one of the many things players had to overcome at the time. A lot of great players never got the opportunity to play in the majors. There were a lot of great players who could have been in the record books.”

Valentine was lucky to play for an Orioles team that was one of the leaders in the American League on the integration front. After serving time in the military, he returned to the Orioles for the 1963 season. In the offseason though, he was sold to the Washington Senators where he had the chance to play for manager Gil Hodges.

“Mr. Hodges was a terrific manager and a nice man, maybe too nice sometimes,” said Valentine. “He was the opposite of someone like Earl Weaver, but he always asked 100% from all his players. He respected everyone and was just a good Christian man.”

Valentine still lives in the Washington D.C. area and has stayed active in the baseball community since his retirement. He was one of the founding members of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association and is currently the Vice President of the group. His old teammate Brooks Robinson is the President. He also lobbied for decades for baseball to return to Washington D.C.

Valentine’s life in sports has roots back to the days where segregation was accepted and expected and spans over 50 years to the current state of full globalization of the sport. He is grateful for the chance to have been a Major League player, even after having to endure so many things fans today couldn’t comprehend.

“It was just a dream that I never thought I’d reach when I was a kid,” said Valentine. “The scouts saw me playing semi-pro ball. I thought I had the tools out of high school, but hadn’t given much thought to it until I started getting some real attention. When I did, that gave me a real interest towards a career.”

Valentine’s name might not come up alongside Robinson, Doby or Paige, but he was truly one of the first wave of black ballplayers to play in the majors. It’s always understood that Robinson was chosen as the first black ballplayer because he had the temperament to gain respect of fans, teammates and opponents. Valentine was the same way. While black ballplayers would have had every right to fight back against the racist taunts they encountered, if they were combative it could have set the movement backwards. He’s one of the few remaining players still alive from that movement, but still continuing to fight for what’s right in the sport.

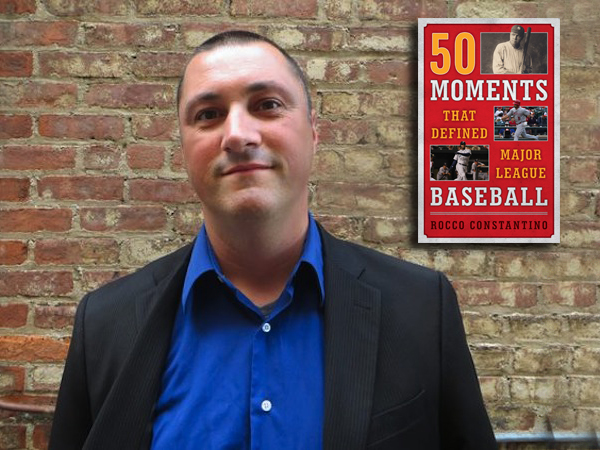

And if you liked this, please look up Rocco’s book, “50 Moments That Defined Major League Baseball”

Rocco Constantino is the author of 50 Moments That Defined Major League Baseball (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) and Featured Columnist at Baseball Hot Corner. He is also a die hard Mets fan going back to the awful early 80’s and ready for the revival. D2 NCAA softball coach and athletics administrator. Follow Rocco on Twitter @mlb100years.

6 Comments

Pingback: The best baseball players born on Jan. 19 – ErbilTimes

Pingback: The best baseball players born on Jan. 19 – Over View – Your Daily News Source

Pingback: The perfect baseball gamers born on Jan. 19 – News247Planet

Pingback: The best baseball players born on Jan. 19 - US News

Pingback: The best baseball players born on Jan. 19 - newsonetop.com

Pingback: The single baseball avid gamers born on Jan. 19 - TS PUBLISHING

You must be logged in to post a comment Login